Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves: Making Sense of the Contradictions of the Founding Fathers

The complex relationship between Thomas Jefferson and slavery has been studied extensively and debated by his biographers and scholars.

The owner of more than 600 slaves throughout his life, Jefferson acquired them by inheritance, marriage, the birth of children to enslaved people, and trade from the time he turned 21. In 1764, he inherited 5,000 acres and 52 slaves after his father’s death. More followed in 1772 upon his marriage to widow Martha Wayles Skelton when her father, John, gave Jefferson two plantations and an additional 135 slaves.

By 1776, Jefferson was one of the largest planters in Virginia. The value of his property (land and slaves) was increasingly offset by his growing debts, which made it very difficult to free them; they were “assets.”

By 1776, Jefferson was one of the largest planters in Virginia. The value of his property (land and slaves) was increasingly offset by his growing debts, which made it very difficult to free them; they were “assets.”

What was Jefferson’s stance on owning slaves? Was it a conflict he wrestled with? Or was it simply a business decision, and a signature of the time?

To find out, Grateful American™ Foundation founder David Bruce Smith and executive producer Hope Katz Gibbs traveled to Monticello, Jefferson’s beloved home in Charlottesville, VA, to interview historian Christa Dierksheide, an expert on Jefferson and slavery. Scroll down to read more.

David Bruce Smith: What kind of slave owner was Jefferson?

Christa Dierksheide: Jefferson was by all accounts a much better master than most. While he did not abolish the use of the whip and corporal punishment, he did try to minimize it. He himself never ordered such punishment, or whipped slaves himself, but we do know that he was not always present at Monticello and that these practices did occur in his absence, especially on the outlying farms. That is just a fact of what Monticello was during Jefferson’s lifetime.

Christa Dierksheide: Jefferson was by all accounts a much better master than most. While he did not abolish the use of the whip and corporal punishment, he did try to minimize it. He himself never ordered such punishment, or whipped slaves himself, but we do know that he was not always present at Monticello and that these practices did occur in his absence, especially on the outlying farms. That is just a fact of what Monticello was during Jefferson’s lifetime.

I think he really did try to reform and alleviate the institution, particularly at Monticello, and make it less coercive and less violent than what he observed elsewhere. We do know from the records in Jefferson’s birthplace, Shadwell, that slavery was much more violent there. Slaves were punished and made to wear iron collars, and one of his father’s overseers killed a slave. Jefferson experienced all that viscerally as a young man, and although he felt that he couldn’t abolish slavery, he tried to improve it in many ways, especially compared to its practice at his boyhood home at Shadwell, which he found quite abhorrent and violent.

Hope Katz Gibbs: Are there any documents or accounts that give us an idea of how Jefferson interacted with the slaves he owned? And what was his daily life like when he was living and working at Monticello?

Christa Dierksheide: Owning the 5,000-acre plantation meant that Jefferson had varied relationships with enslaved people. He was probably, of course, closest to those who performed duties around the house and on Mulberry Row and much less close to those who worked in agriculture, out in the fields.

From the memoir of Madison Hemings, we know that Jefferson was more concerned with manufacturing and light industry — what he called his shops — he would go to the nailery every day and weigh nailrod and assess the effectiveness of the young, enslaved nail boys.

From the memoir of Madison Hemings, we know that Jefferson was more concerned with manufacturing and light industry — what he called his shops — he would go to the nailery every day and weigh nailrod and assess the effectiveness of the young, enslaved nail boys.

Jefferson was involved with much of the light industry that occurred on the plantation; for him this was the future of the plantation. Since agriculture wasn’t as profitable anymore, he had to be highly involved in the enslaved artisans’ daily lives.

Jefferson gave them what he called “gratuities” — tips to incentivize work without the threat of corporal punishment. Two slaves in particular, John Hemings, who ran the joinery, and Burwell Colbert, who was the butler at Monticello, both received $20 a year. These slaves, whom he trusted, were undoubtedly the ones he knew best.

Since we have memoirs from four former Monticello slaves, we have a good idea of how Jefferson was remembered, which was generally positively, but there’s a lot to read between the lines. One of the memoirs recounts a conversation between the Marquis de Lafayette and Jefferson about the topic of slavery.

The two men have differing ideas, with Lafayette being portrayed as in favor of immediate emancipation. Jefferson is instead recounted as accepting the horror of the institution but arguing that it cannot yet be ended, and that alleviation and mitigation of harm are the first steps.

Clearly for that particular slave, the Marquis de Lafayette was more of a hero than Jefferson. Here at Monticello, there is a project called Getting Word, an oral history project that has collected the histories of former slaves and their descendants to shed light on the past and really understand the enslaved as people, because at the end of the day, slavery was about denying the personhood of fellow human beings. Slaves in their time were not considered people, and that needs to be remembered. The Getting Word project is a way to to make sure that, especially here, the past isn’t forgotten.

David Bruce Smith: What did Jefferson do to deal with the problem of slavery?

David Bruce Smith: What did Jefferson do to deal with the problem of slavery?

Christa Dierksheide: Jefferson realized at a very young age that slavery was, again, fundamentally a violation of a person’s natural rights, but also that eradicating an institution sanctioned by law would be very difficult. When he was still a young lawyer in Virginia, when the commonwealth was still a colony of the British Empire, Jefferson took on several freedom suits in which he exploited loopholes in common law that allowed him to emancipate enslaved, oftentimes mixed-race, individuals.

He realized, however, that he was up against enormous opposition, because most whites across America were in favor of some kind of free labor — such as indentured servitude or outright slavery — and that it would take a long time for a cultural shift of such a magnitude to occur. He did propose legislation to liberalize manumission (the freeing of enslaved people by their owners), supported legislation that would abolish the transatlantic slave trade with Virginia, and in both “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” and the Declaration of Independence addressed British King George the III and accused him harshly of imposing the slave trade on Virginia and disallowing Virginians their rights to prohibit it. Despite all this, he was unable to make political inroads in the problem of slavery after the Revolution, because the federal government interfering with private property, as slaves were considered, was a central tenet against which the American Revolution was fighting. This made it extraordinarily difficult to convince slave owners that government should be allowed to tell them what to do.

David Bruce Smith: How do you think Jefferson would have felt about the evolution of civil rights and also women’s rights?

Christa Dierksheide: Jefferson is our modern champion of universal rights, but in his own day those rights would in no way have been universal. Jefferson was in favor of the equality and liberty of men like himself: elite white men. He believed they should be free and equal, but the enslaved, women, and minorities were not part of that vision of equality and freedom. In our day, those iconic words of the Declaration of Independence have become central to human and civil rights movements in the 20th century, showing how elastic and inclusive those ideas can become over time, but in his own time they did not apply to all.

David Bruce Smith: Would he have felt the same way about his wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson?

Christa Dierksheide: Jefferson believed that the education of his daughters would include them becoming plantation mistresses; they would be educated in music, arts, and the way of governing a plantation, but they would never lead or govern a plantation independently. The structure of governance in Jefferson’s era within a household like the plantation — these 5,000 acres around us — was comprised of hundreds of people, all of them dependents except one, Jefferson himself. Of all the slaves, women, and the poor whites who lived on Monticello, only Jefferson was an independent man, who therefore had the capacity for freedom and rational thinking.

He believed that all of those dependents could never be like himself since independent patriarchs had to have had certain education, and certain social status, and frankly they had to be, in the 18th century, white males. Oftentimes people don’t realize that household governance, comprised of dependents with a single independent patriarch, was the system that governed early America. The ideas of liberty and self-government that Jefferson espoused in the Declaration weren’t to be grasped by dependents, only by independent men like himself.

He believed that all of those dependents could never be like himself since independent patriarchs had to have had certain education, and certain social status, and frankly they had to be, in the 18th century, white males. Oftentimes people don’t realize that household governance, comprised of dependents with a single independent patriarch, was the system that governed early America. The ideas of liberty and self-government that Jefferson espoused in the Declaration weren’t to be grasped by dependents, only by independent men like himself.

Hope Katz Gibbs: So this all begs the question about Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings.

Christa Dierksheide: Correct. Historians know that many years after his wife’s death, Jefferson did have a relationship with Sally Hemings that resulted in six children.

Christa Dierksheide: Correct. Historians know that many years after his wife’s death, Jefferson did have a relationship with Sally Hemings that resulted in six children.

These sorts of relationships between master and slave were not uncommon and invariably non-consensual since the persons of half the relationship were considered property. From documents or archaeology we don’t know the specifics about Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings. There has been a variety of speculation, but she certainly did live in close proximity to Jefferson’s chamber for most of her adult life.

In fact, all members of the Hemings family were deeply interwoven with Thomas and Martha Jefferson. Sally Hemings’ mother was the result of a union between Martha’s father, John Wayles, and Elizabeth Hemings. It’s hard to know the specifics of their daily interaction, but it does present the time as more racially complex, which has of course affected America many years into its future, and, again, part of what we are trying to preserve here.

For more information about Thomas Jefferson, visit Monticello.org.

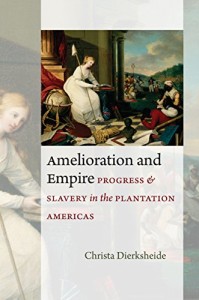

About Christa Dierksheide: Dierksheide earned her PhD from the University of Virginia (UVA) in 2008 and is now a staff historian at Monticello. She has just published “Amelioration and Empire: Progress and Slavery in the Plantation Americas” with UVA Press.

About Christa Dierksheide: Dierksheide earned her PhD from the University of Virginia (UVA) in 2008 and is now a staff historian at Monticello. She has just published “Amelioration and Empire: Progress and Slavery in the Plantation Americas” with UVA Press.

The book “argues that ‘enlightened’ slaveowners in the British Caribbean and the American South, neither backward reactionaries nor freedom-loving hypocrites, thought of themselves as modern, cosmopolitan men with a powerful alternative vision of progress in the Atlantic world. Instead of radical revolution and liberty, they believed that amelioration — defined by them as gradual progress through the mitigation of social or political evils such as slavery — was the best means of driving the development and expansion of New World societies.” Click here to learn more.