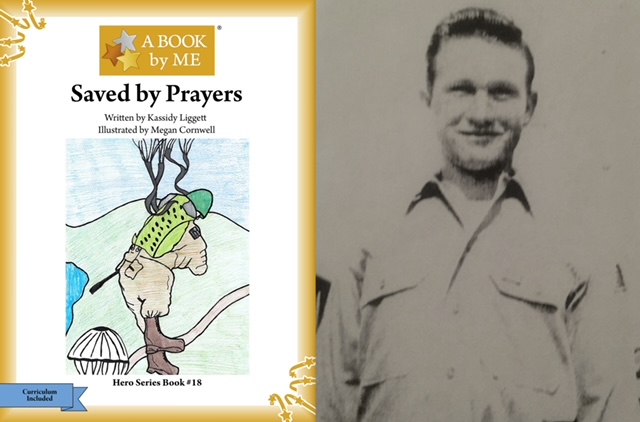

Saved by Prayers: Henry Langrehr, 82nd Airborne Division

Written by Kassidy Liggett and Illustrated by Megan Cornwell

For the series A BOOK by ME - True Stories Written by Kids for Kids

WWII Veteran Henry Langrehr

Have you ever heard the saying “I almost fell off my chair?” I’ve heard that a few times in my life but only one time did I feel like I was going to do it. It happened toward the end of an interview with WWII Veteran Henry Langrehr and two eight grade girls who were going to write and illustrate his story.

Along with 16,000 others, young Henry parachuted into France. He had 150 pounds of explosives and materials on his back and soon realized they were off course. They landed in a village in northwest France that was occupied by the enemy. He was in trouble and he knew it. His story is like an action movie and to me, Henry is like a teenage Rambo. Here’s what we heard:

His friend Private John Steel from Illinois got his parachute hung up on the steeple of a church and faked dead. That’s how he survived. Henry crashed through the glass roof of a greenhouse. If this sounds familiar, it was a scene in a movie with John Wayne called The Longest Day. During the battle that followed, two of his friends died in his arms. They both quoted Bible verses he was not familiar with since he didn’t go to church. Death was all around him as he fought through the hedgerows of Normandy. One day Henry passed out. He woke up a prisoner of war in a boxcar packed very tightly with no room to move. Two days went by for the 100 men on board with no food or water. Their captures had changed their plans since the Allies bombed the rail system near a chemical plant. Their train stopped right outside the gate of Auschwitz concentration camp. The Nazis strung barbed wire by the gate and the prisoners sat in the dirt. For days Henry and the others watched the Jewish people walk into the shower house to be gassed and carried out naked dead bodies. The workers stacked them four or five feet high. Finally they left when their train was rerouted to a coal mine in Czechoslovakia.

Their commander hated Henry for challenging him that he wasn’t living up to the standards set by the Geneva Convention. He was hit with the butt of a gun. Henry thought the Nazi commander may kill him so he and his friend Tim decided to escape. They ran into the countryside and the Nazi militia was chasing them. They ran into a barn and hid. Tim was found and killed that day. Now alone, Henry ran through a freezing cold stream to throw off the scent of the German shepherd dogs. He traveled for weeks, moving at night using the stars to guide him. He came upon a town and went into a building with four Nazis inside. Henry said he took care of them. At this point I had to stop and ask what he meant by that and that sweet man looked me in the eye and said “I killed them all”. Back in Iowa, he went straight into the arms of his girlfriend Arlene. She’d prayed for him every day. Henry remembered men dying all around him during the war and wondered, “Why not me?” After hearing how she’d prayed, he knew he was saved by her prayers.

It was the point that he single-handedly killed four men that I almost fell off my chair. I thought I might when he described the experience at Auschwitz. How that man didn’t freeze to death, I do not know. I came to the same conclusion, he was saved by the prayers of the woman who loved him. That night as we left, Henry told the girls “if anyone denies the Holocaust they aren’t living in the real world, I saw it.”

God bless America.

Deb Bowen, A BOOK by ME

Saved by Prayers

Henry Langrehr was a paratrooper who crashed through the roof of a greenhouse (as seen in the movie “The Longest Day”). He was captured as a prisoner of war (POW) and became an eyewitness to the horrors of Auschwitz concentration camp. Available from Amazon.

Henry Langrehr, 82nd Airborne Division

Henry Langrehr was born in Clinton, Iowa on November 4, 1924. He was raised during the Great Depression, and his father worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a program created in 1935 under President Roosevelt’s New Deal.

After the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, Henry, age 17, was not old enough to join the service. But, right before his eighteenth birthday, he quit high school along with forty percent of his class. He asked his girlfriend, Arlene Ketelsen, to marry him but decided to wait for the wedding until he came back from the war. He volunteered as a paratrooper because it paid $50 per month more.

Henry shipped overseas on the Queen Elizabeth, the fastest ship at that time. He landed in Belfast, Ireland, traveled to Oxford, England, and then to a small village. The young soldiers stayed in homes with families until their tents were set up. England had been in the war since 1939, and citizens were so thankful to have the “Yanks” in their midst. It increased their faith in winning the war. Henry enjoyed handing out Wrigley’s chewing gum and chocolates to the children.

As part of the 82nd Airborne Division, Henry was one of 16,000 men who parachuted into France early in the morning of June 6, 1944 on a beautiful moonlit night. He weighed 150 pounds and had that much weight in material strapped to his back. He also had a rope around his ankle carrying explosives. He was assigned to blow up a bridge once they landed. The men sat on benches facing one another waiting for their time to jump.

As they got closer to France, a gun shell landed on the wing. It instantly killed the man across from Henry and the person sitting beside him. The paratroopers jumped, but they were five miles off course. They landed in Sainte-Mère-Église, a German-controlled village in the northwest of France. Many men landed in the trees and were shot by the German army. Henry was friends with Private John Steele from Metropolis, Illinois whose parachute was caught on the church tower. John feigned being dead, which saved his life. Henry crashed through the glass of a greenhouse. Among the chaos, Henry found the explosives. He loaded them onto a Kettenkrad, a German motorcycle used during the war.

During the battle, two good friends were shot and died in Henry’s arms. Both were men of faith and recited Bible verses before they died. Henry remembers the look of peace on their faces as they passed away and wished he had that kind of peace, too. Death was all around him. He fought through the hedgerows of Normandy. The hedgerows were mounds of earth designed to keep cattle in and to mark land boundaries. They were various heights and sometimes met overhead like a tunnel. Many men were separated from their units, and it was frightening being there alone. His unit met German soldiers who surrendered. The Americans disarmed them. This went on through the end of June. One day, Henry shot a panzerfaust, a German version of the American bazooka gun. He passed out and awoke as a prisoner of war (POW).

Henry and about a hundred others (Americans, British, Polish and Russians) were loaded onto boxcars, packed very tightly for two days with no room to move, no food or water. The German’s plan changed when the allies bombed a chemical plant. The train stopped just outside the gate of Auschwitz concentration camp, and the Nazis set up a temporary camp. There were no bathrooms, and the conditions were deplorable as themen watched what was happening to the Jewish people in the camp. Henry saw naked, dead bodies with shaved heads brought out of a gas chamber on carts and stacked four or five feet high. When asked in 2016 what he would say to someone who denies the Holocaust, Henry said, “They aren’t living in the real world. I saw it.”

Later, the POWs were taken by boxcar to a coal mine in Czechoslovakia where Henry worked for over eight months at forced labor. The men stayed in a big factory, and the Nazi Commander often reminded them: “Nobody escapes from this camp.” Some men tried and were killed. Henry worked underground in the mine with an older Czech man. Henry tried to reason with the SS Guard that the conditions did not live up the Geneva Convention on the treatment of civilians and prisoners of war. For that, Henry was hit with the butt of the rifle. This happened two days in a row and finally the Czech man advised, “Work or be killed.” The prisoners were fed beet soup and bread made of sawdust.

One day, Henry and his friend Tim escaped and headed west to where they knew the Americans were located. There was a German Volkssturm chasing them. A Volkssturm was a member of the German national militia. The Nazi Party established the militia during the last months of World War II on the orders of Adolf Hitler, not by the traditional German Army.

Henry and Tim ran into a barn on the outskirts of town where Henry hid behind the door. When the Volkssturm entered, he killed Tim. Henry was unarmed but he picked up a two-by-four and hit the Nazi across the head. Henry took the pistol and ammo and left. He ran through a frigid stream, which threw off his scent for the German shepherd dogs that were after him. After two miles, he was afraid of hypothermia (freezing to death). He hid in a cemetery. Since he hadn’t eaten or drank in days, he picked up a vase of flowers and drank the water inside. It tasted horrible, but it kept him alive. He traveled for two weeks, moving at night and using the stars to guide him. He came upon a town and went into a building with four Volkssturm inside. Henry caught them by surprise, killed them, and took their cheese. Another time, he went into what he thought was an abandoned farmhouse. Two Volkssturm came up from the basement, but Henry was able to overpower them. He could hear the Allies’ artillery firing in the distance. He decided to hide 500 yards off the road and wait for the Americans to come by. Immediately, he was taken to a first aid station called Camp Lucky Strike (named after a cigarette). He weighed a mere ninety-nine pounds and was full of lice. After treatment, the military sent him back to America.

In Iowa, he went straight into the arms of Arlene. She had prayed for him every day. Henry remembered men dying all around him during the war and often wondered, “Why not me?” His fiancé asked him to pray a prayer asking Christ into his life. He has lived with faith every day since then. Henry married his sweetheart on July 1, 1945. She was working in a factory making machine gun parts like many other women working men’s jobs during the war. These women are often called “Rosie the Riveter”. During this time, almost everything was rationed for the war, but family members combined their stamps to buy flour to make a wedding cake. Henry was one of the first men home from the war, and his experiences on D-day were depicted in the first movie made about Normandy. The Longest Day, starring John Wayne, portrays a young man crashing into the glass roof of a greenhouse. That man, in real life, was Henry Langrehr.

Arlene and Henry built their home, and he worked in contracting. They raised four children together in Clinton, Iowa. Today, Henry says, “The Lord has his hand in my life. He guided me through and saw me home. He had a purpose for me, and that purpose was my family.” After the war, the U.S. Army awarded Henry two Purple Hearts and many other medals. Sixty years later, he was honored in Washington D.C. by French President Nicholas Sarkozy on September 28, 2007. In honor of the 60th anniversary of D-day, Henry was named a knight of the Legion of Honor for his actions during World War II. This is the highest honor that France can bestow upon those who have achieved remarkable deeds for France and a sign of true gratitude for servicemen’s invaluable contribution to the liberation of France during WWII.

Hero Henry Langrehr in front of his many medals

Hero Henry Langrehr with the Middle Schoolers who preserved his story for young readers.

A BOOK by ME, a book series developed by Deb Bowen, empowers students to preserve history by telling the story of unsung heroes in our communities. For the young participants, it’s a guided cross-curricular project that gathers stories of people who do amazing things but have received little or no recognition. Students learn how to publish a picture book that is a primary source document with photographs and a biography.

A BOOK by ME, a book series developed by Deb Bowen, empowers students to preserve history by telling the story of unsung heroes in our communities. For the young participants, it’s a guided cross-curricular project that gathers stories of people who do amazing things but have received little or no recognition. Students learn how to publish a picture book that is a primary source document with photographs and a biography.

Since 2003, Deb Bowen has been arranging meetings between students and individuals from the WWII generation. This intergenerational storytelling results in unique storybooks written and illustrated by kids for kids in the A BOOK by ME series. More about Deb Bowen >