The Soldier Who Forgave: The Story of Leland Chandler, WWII POW

Written by Hannah Edwards & Le’Char Morgan

Illustrated by Rafael Estrada & Garrett Carroll

For the series A BOOK by ME - True Stories Written by Kids for Kids

I had the honor of meeting with this amazing WWII hero named Leland Chandler several times. On one occasion, it was Leland, a Rosie the Riveter named Julia Mattocks and a bombardier named Reed Robertson all together at a school. Three WWII heroes in one room. As we were chatting, Julie mentioned working for a time at a munitions factory filling bombs. She said she prayed each day “Lord, don’t let these bombs fall on innocent women or children.” I could see the look of pain on Reed’s face. He’d seen those bombs fall – including the A Bomb which he’d photographed from the air and later the aftermath on the ground. Also, the look on Leland’s face as a POW in Japan waiting for the Allied victory. The enemy did everything they could to break their prisoner’s spirit. It was a true test of endurance, hope and courage for the prisoners. Leland and the others are a true testament of the power of resilience and perseverance in the most challenging of circumstances. Both Julia and Reed have passed away but Leland is still alive and he welcomes getting cards and letters. Please see our “Write a Hero” program and make his day with a note of thanks. God bless our veterans for all they’ve done for the freedoms we enjoy.

Deb Bowen, A BOOK by ME

FYI – Leland is 101 years old (01/03/1923) WATCH!

“You may know a hero in your life, and I bet you do. True heroes forgive their enemies and have the courage to do what is right, no matter what. True heroes hold onto their faith in the hardest of times. True heroes inspire and encourage you. Firefighters, doctors, police officers – they are all heroes. But, this story is about another kind of hero, Leland Chandler, and we should all thank him for his courageous service.

Authors Le’Char Payton & Hannah Edwards

We wish to dedicate Leland’s book to all WWII veterans who are part of the Greatest Generation. We are amazed at the sacrifice, endurance, dedication and strong spirit shown by these American heroes.

We would like to thank Pam Johnson for walking us through the writing and editing process. Pam is the Regent of the Rebecca Parke Chapter of the National Society of Daughters of American Revolution (NSDAR). This organization holds patriotism in high esteem, and Pam shared that passion with us.”

Happy Reading,

Hannah Edwards & Le’Char Morgan

“I think all veterans should be remembered and honored. This new generation should study the sacrifices and the accomplishments of our veterans. I’m very grateful for this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Illustrator Rafael “RJ” Estrada

Illustrators Rafael Estrada & Garrett Carroll

Leland Chandler – Japanese POW from Corregidor

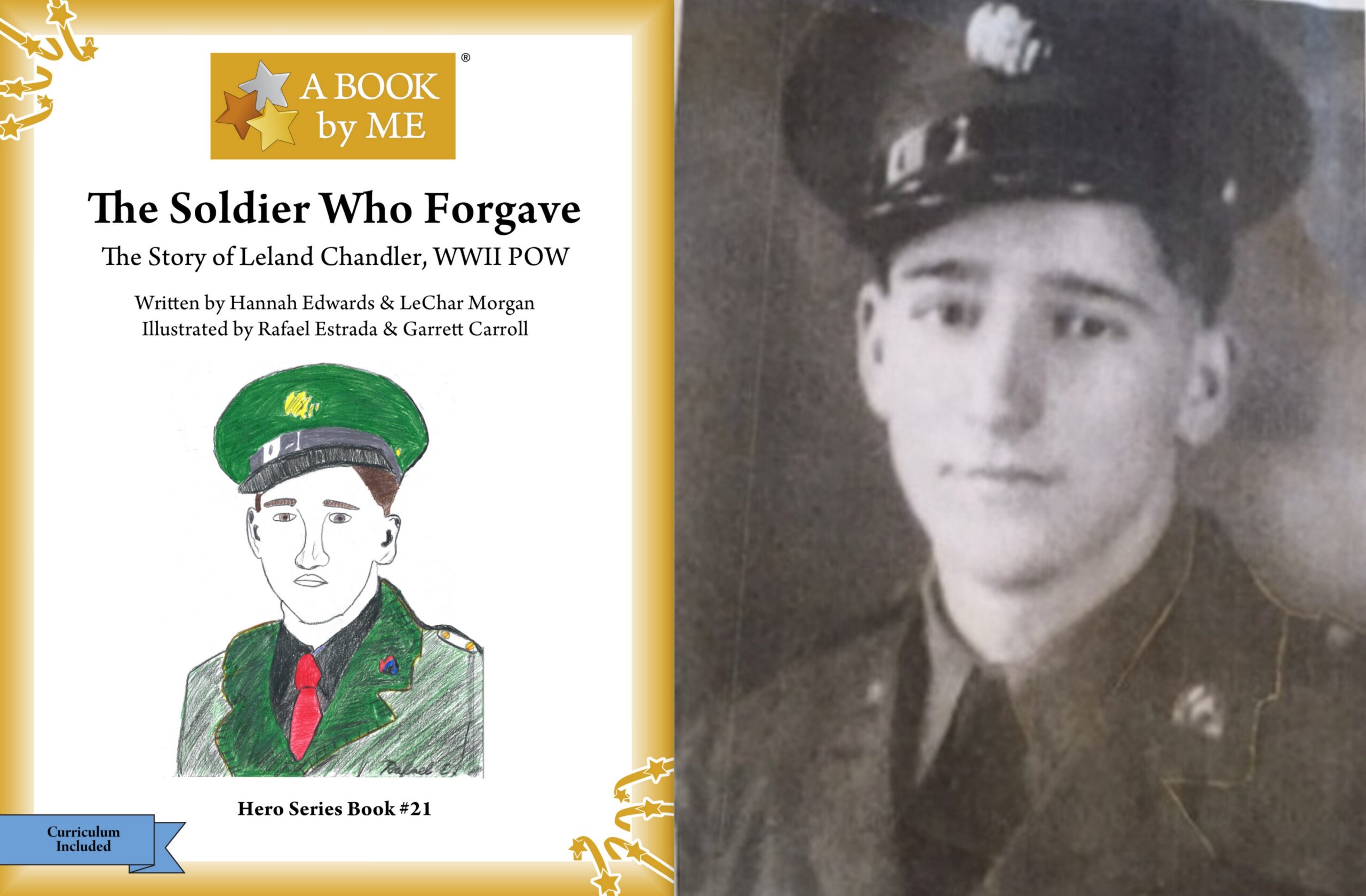

Leland Chandler, Japanese Prisoner of War (POW), was born in a small farming town called Table Grove, Illinois on January 3, 1923. As a child, he walked one and a half miles each day to attend a one-room school until the eighth grade. Leland drove seven miles to attend high school, but he did not finish. The military seemed to be calling him to service.

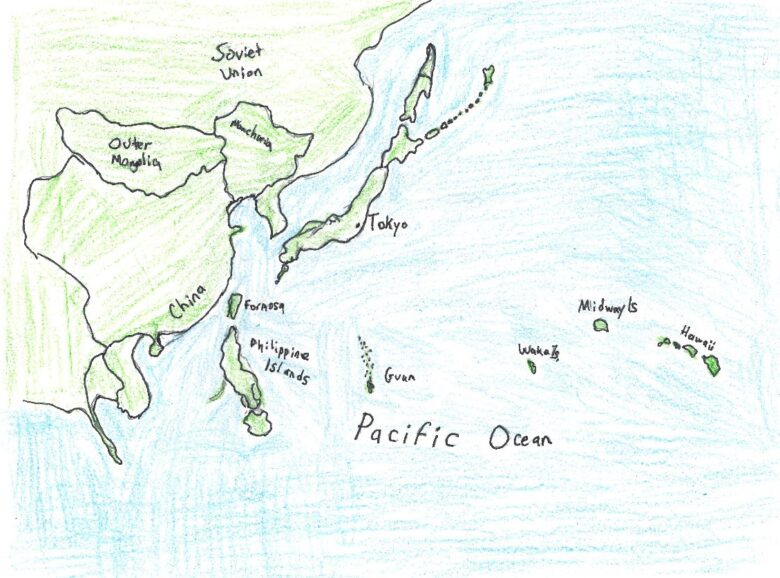

At the age of 18, he enlisted in the army and was immediately sent to San Francisco, California in 1941. From Angel Island, he sailed on the USS Republic to the Philippine Islands with 2,200 other men. After arriving in Manila, he was placed in the 60th Coast Artillery H Battery in Corregidor. Soon, Corregidor, an island two miles wide and one mile long, was the training ground for these men as they learned to use heavy anti-aircraft guns. The military was sure the Japanese would be attacking soon because the Japanese air patrol and navy were buzzing with activity.

At the age of 18, he enlisted in the army and was immediately sent to San Francisco, California in 1941. From Angel Island, he sailed on the USS Republic to the Philippine Islands with 2,200 other men. After arriving in Manila, he was placed in the 60th Coast Artillery H Battery in Corregidor. Soon, Corregidor, an island two miles wide and one mile long, was the training ground for these men as they learned to use heavy anti-aircraft guns. The military was sure the Japanese would be attacking soon because the Japanese air patrol and navy were buzzing with activity.

On November 28, 1941, the men were ready to eat their Thanksgiving meals when the general alarm sounded. Everyone went into battle positions on Corregidor, on nearby Bataan, and on Guam and Wake Islands. Surely, they thought, the Japanese were going to attack these main American defenses that protected the Philippines. Word was sent to Hawaii, but that message was ignored. Instead of attacking near the Philippines, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th. Thousands of American lives were lost because of the fatal communication error.

Then, on December 8th, the Japanese bombed the Philippines, and they landed on Leyte Island in the Philippines on December 20th. For some reason, General Douglas MacArthur did not follow the war plan set out by the War College, so the army lost a lot of hospital supplies, food and equipment. After the bombing occurred in December, MacArthur had declared Manila, the Philippine capital, an open city on Christmas Day, thinking that the Japanese would not bomb it. As it turned out, this was another disastrous mistake. Because the Japanese were taking over most of the Pacific islands and countries, President Roosevelt sent MacArthur immediately to Australia to protect the Southern Pacific. When he left, he promised that he would return. His promise was too late to help thousands of Americans and Filipinos.

As MacArthur was preparing to leave the Philippines, he asked if any of the nurses wanted to go with him. These nurses were as loyal and determined as many of the brave men that were fighting. All but one elderly nurse refused, as they wanted to be present if any of the soldiers needed medical attention. Meanwhile, the Japanese pummeled the islands daily with a constant barrage of gunfire, but MacArthur was able to get out in time. Bataan and Corregidor were left to fight under constant attack.

After General MacArthur left, General Wainwright took over. The men loved and respected this man. He was honest in telling them what to do, since no one was able to come to relieve them, and they were under constant attack. The Japanese soldiers outnumbered the American and Filipino soldiers by 100 to 1. The Philippine army, 1000 Constabulary, had been trained by MacArthur to protect the Philippines, and they were loyal soldiers who fought on the front lines with the Americans. Philippine Scouts were also trained by the U.S. Army.

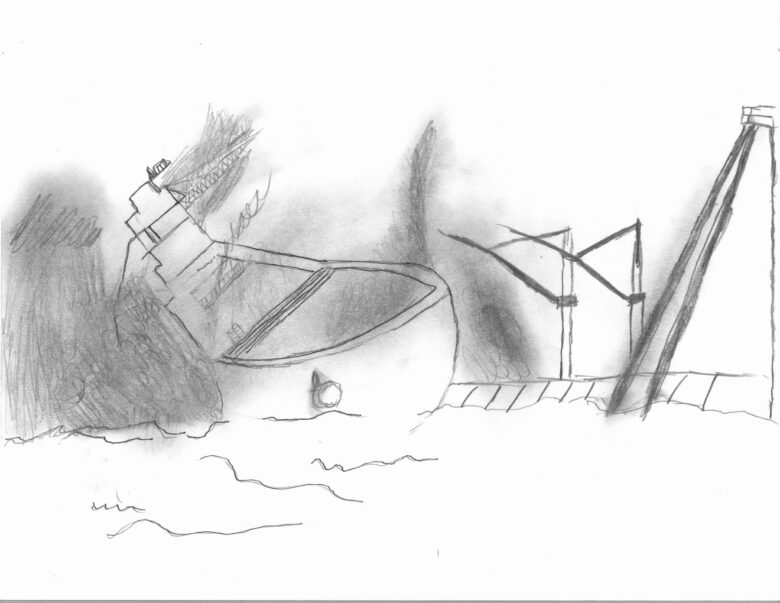

As the fighting became intense, many American and Filipino soldiers swam or escaped by boat from Bataan to Corregidor. Sadly, Bataan was taken over on April 6, 1942, with 5,000 men taken prisoner. The Japanese forced these men on a “death march,” where they were kept walking for days. If prisoners fell, they were instantly shot. Many men were brutally killed if they did not march or obey their captors. Over 800 American men died on that march.

On Corregidor, Leland’s Battery continued fighting for another month but was forced to surrender on May 6, 1942. It was a horrible scene for these men and women who stayed to defend this area. Even the brave nurses who stayed were brutally tortured. Everyone, including soldiers and Army nurses, were taken to Cabanatuan Camps in Manila by ship. In Manila, they were forced to march through the streets so the Japanese would show the nationals how strong and powerful they were.

Then, the prisoners were placed on ships headed to Japan, which were so crowded that there was no room to sit or move. The Japanese stuffed the prisoners into these “hell ships” where it was difficult to move or breathe. Because they were forced to drink filthy water and eat meager rations, many died. The ship that Leland was on held about 2,000 prisoners.

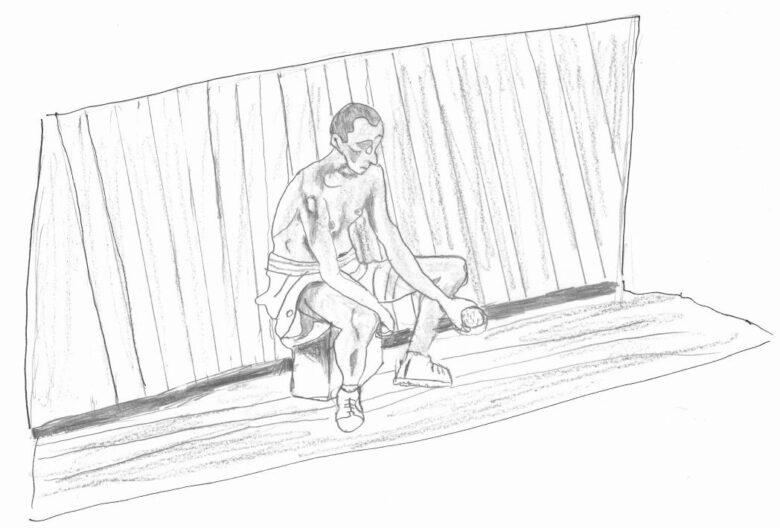

After reaching Japan, the strongest men, about 400 Americans (including Leland), were taken to Yodogawa Steel Mill in Osaka. For 3½ years, Leland was forced to work 12-hour days as a slave laborer. He was given half of a bowl of rice in the morning and half of a bowl of rice at night. That was all. If men did not work, they did not eat. Speaking in English was forbidden; if prisoners did so they were severely punished.

In Osaka, Leland remembered that there was no shelter for living quarters. Instead, the prisoners were forced to sleep on the hard floor of the steel mill each night. Because of the severe abuse and conditions, Leland does not often speak of the beatings given him as a prisoner.

During roll call, each prisoner was assigned a number that he was to learn in Japanese. If he did not learn it, he would have his tongue cut out. Many prisoners gave up and later died; then a new number was assigned to each prisoner. It was hard to keep up with learning these new numbers. Leland remembers that he had his face slapped and cut because he did not know the new number. Thankfully, he learned quickly.

When the men knew they were going to be liberated, and the war was coming to an end, the Army Air Force was able to drop barrels of food, clothing and Hershey candy to them. Out of 400 prisoners, only 52 survived. To put things into perspective: Leland weighed 190 pounds when he joined the army in 1941. After being rescued from Osaka, he only weighed 85 pounds.

A strange thing happened to Leland on the day of liberation. Earlier in the war, his Bible was stolen. This was a special Bible his father carried during WWI, which was given to him when he enlisted. On the day Leland was freed, he found that Bible lying on his sleeping mat. This Bible was special because Leland believed it contained God’s Word that built his faith when he needed it the most. Later, when his son went to Korea, Leland gave that special Bible to him.

After the war, Leland was married to Ruth and became a firefighter for a Military Medical Transport in Moline, Illinois. When that business closed, he worked as a firefighter in Galesburg for the University of Illinois Annex near the Hawthorne Center. Finally, Leland worked at the Chanute Air Force Base in Rantoul, Illinois and retired as the Fire Chief. After 31 years as a firefighter, he and his wife settled in Galesburg, Illinois.

The army gave Leland many awards and honors for his courage and bravery in Corregidor during WWII, but he treasures the three Presidential Citations the most.

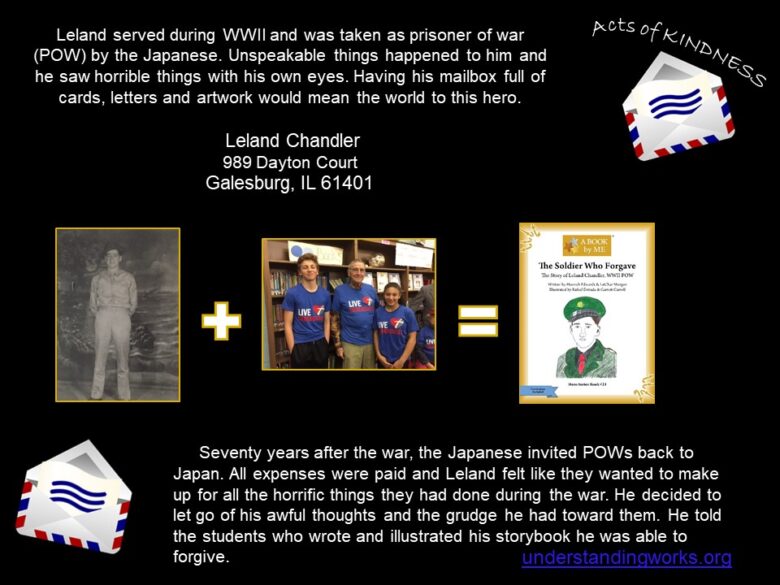

Seventy years after the war, the Japanese invited many of the surviving POWs back to Japan for a ten-day, first-class visit of all the sites. By that time, there were very few POWs left. But these men were treated like royalty by the Japanese. Leland was able to take his dear wife, Ruth, with him on that trip. He even returned to Yodogawa where he saw many new buildings and structures. The landscape had completely changed. The hospitality of the Japanese made it seem like they wanted to make things up to the American POWs for what they had done during the war. Leland decided that he was not going to hold a grudge against them. He felt it was better to forgive and not continue holding onto his awful thoughts and emotions.

Leland Chandler joined the Army during WWII and served in the Pacific theater. He was taken as a prisoner of war by the Japanese and treated horribly. Seventy years after the war he was invited back to Japan where he learned to forgive the sins of his former enemies.

A BOOK by ME, a book series developed by Deb Bowen, empowers students to preserve history by telling the story of unsung heroes in our communities. For the young participants, it’s a guided cross-curricular project that gathers stories of people who do amazing things but have received little or no recognition. Students learn how to publish a picture book that is a primary source document with photographs and a biography.

Since 2003, Deb Bowen has been arranging meetings between students and individuals from the WWII generation. This intergenerational storytelling results in unique storybooks written and illustrated by kids for kids in the A BOOK by ME series. More about Deb Bowen >