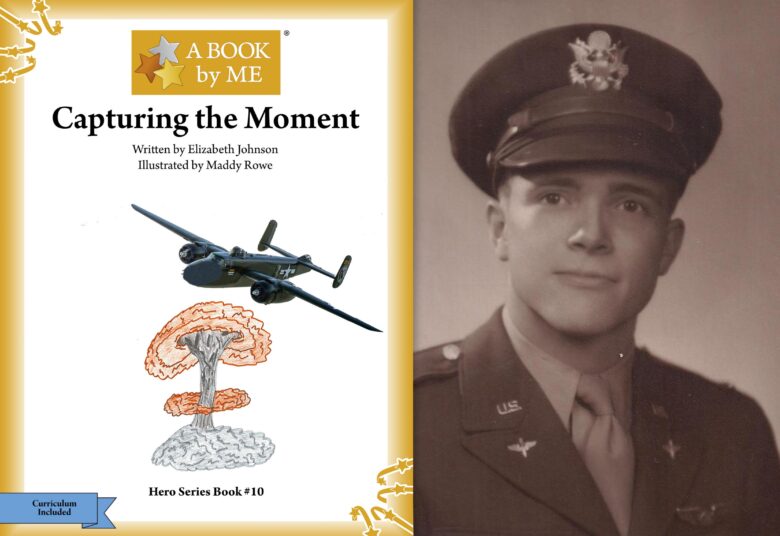

Capturing the Moment

Written by Elizabeth Johnson

Illustrated by Maddy Rowe

A BOOK by ME - True Stories Written by Kids for Kids

Meeting Reed Robertson and hearing the story of his service in the Pacific Theater in WWII was so interesting. He played a big part in capturing the history of the A bomb being dropped on Hiroshima with photography. Then, on September 2, 1945, his crew ordered to fly over and take pictures of Japan’s formal surrender aboard the U.S.S. Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. Such amazing historical events.

I’m currently creating more Readers Theater scripts for students across the nation to act out for America250. Reed Robert’s story is one I’m creating a script for right now. One of my favorite parts of his story was his grandfather’s work with the William Penn statue that can be seen by all on the top of City Hall in Philadelphia. Here’s a small part of the script that talks about that fun memory that his grandfather shared with him years ago. Veteran Reed Robertson told me about it with much laughter. This is going to be part of the new script:

- William Penn: I was watching from heaven above while those girls circled my hat on the ground. I marveled how they embodied the spirit of the very ideals I championed: freedom, joy, and the promise of a better future. Each step they took around that brim was a reminder of the hope and possibility that I sought to instill in the new colony I called Pennsylvania so many years before. It was a living testament to the legacy of unity and diversity that I hoped Pennsylvania would always represent.

William Penn Statue located on top of Philadelphia City Hall

As we celebrate America250, it is my hope and prayer that Americans come together in unity and purpose. Let us reflect on our shared history, honor the sacrifices of those who came before us, and embrace the diverse tapestry that makes our nation strong. May we foster understanding, compassion, and respect for one another, transcending our differences and working hand in hand toward a brighter future for our children and our grandchildren.

Deb Bowen

Executive Director Understanding Works

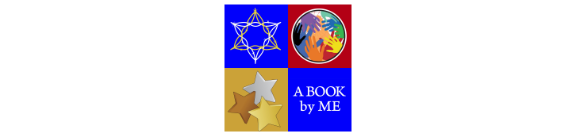

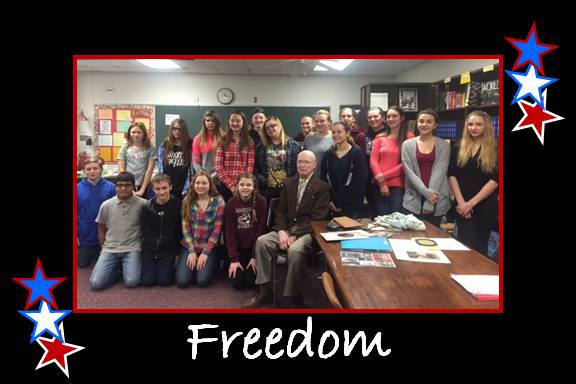

Reed Robertson at Rockridge Junior High School (2016)

Reed Stuart Robertson — 345th Bomb Group Air Apaches

Reed Robertson was born on August 19, 1921 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city rich in American history. Reed’s Scottish grandfather, Robert Reed Robertson, was the architect who set the famous statue of its founder, William Penn, on top of city hall. Before this 37-foot-high bronze statue was installed, the architect’s daughters walked around the hat’s brim while it was separate and standing on the ground.

Reed Robertson born August 19, 1921

Reed’s mother, Hannah Marion Stuart, and his father, Clarence Herbert Robertson, were both known by their middle names. Reed had two sisters, one two years younger, one two years older. He used to say he was “the thorn between two roses.” Both sisters were stricken with very serious illnesses that made life hard for everyone, especially their mother.

Marion’s mother, a self-taught artist, sent her daughter for formal training at an art school in Philadelphia. Marion continued to do art projects throughout her life. She did many jobs inside and outside the home to earn money to help support the family during the Depression. She enjoyed playing the piano every morning. Reed often joined her to sing hymns. Their upright piano was also a player piano, which provided added fun for the whole family.

Herbert was an export/import manager at a company in Philadelphia. He lost his job at the start of the Depression. The family had just moved to Collingswood, New Jersey. The job loss caused them to sell their house and car and move to a smaller house, with lower taxes, three blocks away. Herbert started two businesses that each failed because of lack of capital. He had been a good father who did many things with the children, including taking them on trips to Philadelphia to see sights he had enjoyed while growing up in the city. He and Reed listened to the radio together. After Herbert’s business failures and the girls’ illnesses, he became depressed. Things were never the same.

Reed did many jobs to help make ends meet. He sold magazines, such as the Ladies Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post and Country Gentlemen. With some earnings, he bought a bike to make his work easier. When the banks failed in 1933, like so many others, Reed lost money he had saved. It’s estimated that 4,000 banks failed that year alone.

As a young boy, friends and neighbors gave Reed toys that were luxuries in those days, such as a chemistry set and, later, a child-size pool table. Young Reed wanted to fly, a dream that would come true, but not in the way he imagined. During his free time, he ran at the high school track and played baseball and football with friends on vacant lots. But, mostly, he was trying to earn money and studying. When he graduated high school, he went to Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia, using a $200 scholarship he was awarded. He was studying chemical engineering. Part of his curriculum included an internship at DuPont, a world-class chemical company.

Reed was in college when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Now America was at war. In November 1942, Reed enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He was called up in January 1943 and sent to basic training in Florida. After that, he was sent to Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois as a part of a new special military program to groom future offcers in leadership skills. One day, in the college library, he met a young woman named Audrey. After, he was next sent to San Antonio, Texas, he and Audrey wrote each other. In San Antonio, Reed faced the choice of becoming a pilot, a navigator or a bombardier. He chose to become a navigator.

Reed enlisted in the Army Air Corps, November of 1942

While he continued to train to go to war, his thoughts were often of Audrey. Ironically, part of his training eventually included bombardier school in New Mexico. He also spent time training others in basic navigation skills. When he got leave, he went to Rock Island, with an engagement ring, and asked Audrey to marry him. A few months later, they were married on November 17, 1944.

In January 1945, Reed was shipped to the South Pacific. His Stateside training crew had named themselves “23 Skidoo” because, except for the tail gunner, they were all 23 years old. “Skidoo” was the nickname given to the tail gunner. But, once overseas, no one in Reed’s unit flew with their original crew members. On the way, Reed stopped in Hawaii and then went on to New Guinea, where the weather was hot and humid, the birds were strange-looking, and there were stories and evidence of head-hunters. The Americans were occasionally bombed by the Japanese. When the Allies pushed the Japanese back into the hills of the Philippines, Reed’s unit was moved to the Philippines. He wrote Audrey every day, sometimes including a pressed flower in his letter.

Reed became a part of the 345th Bomb Group, nicknamed the Air Apaches

Being a navigator was a job with a very high death rate. Navigators, using a parachute for a seat, sat behind the pilot. There was very little protection, limited equipment to do the job and tight quarters. On many occasions, this caused Reed to think, “I’m not going to make it.” His unit did low altitude skip bombing and strafing. Sometimes, they were ordered to take photographs from the air.

His unit belonged to the 345th Bomb Group, nicknamed the Air Apaches. Reed remembers hearing the woman named Tokyo Rose mocking them on the radio. She was an American-born daughter of Japanese immigrants, but spent the war years with relatives in Japan. Her propaganda radio program, “Zero Hour,” was aimed at demoralizing American troops. She was eventually returned to the United States after the war and tried for treason.

Several days after the August 6, 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Reed’s plane crew received orders to fly over Hiroshima to take aerial photographs of the damage. Then, on September 2, 1945, they were ordered to fly over and take pictures of Japan’s formal surrender aboard the U.S.S. Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. Much later, after the surrender, when going from one location to another in Japan, Reed walked around Hiroshima near the train station and saw the damage up close.

When Reed came home, he and Audrey moved to the Chicago area where he took advantage of the GI Bill. He went to night school to complete his college education at the Illinois Institute of Technology while working full-time at National Aluminate Company, now known as Nalco. They had a good life, which included a daughter, Cynthia, and eventually two grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Reed worked for Nalco for 38 years. Audrey was a teacher for 13 years. In 1984, they moved to Damariscotta, Maine. They moved back to Illinois in 1998 to be near their daughter and her husband in Galesburg, Illinois. Audrey passed away in 2014. Reed continued to live in Galesburg until he passed in 2018 at the age of 97.

A BOOK by ME, a book series developed by Deb Bowen, empowers students to preserve history by telling the story of unsung heroes in our communities. For the young participants, it’s a guided cross-curricular project that gathers stories of people who do amazing things but have received little or no recognition. Students learn how to publish a picture book that is a primary source document with photographs and a biography.

Since 2003, Deb Bowen has been arranging meetings between students and individuals from the WWII generation. This intergenerational storytelling results in unique storybooks written and illustrated by kids for kids in the A BOOK by ME series. More about Deb Bowen >